The Civil War Comes to the Clarks in Tivoli

by P. Clarke Glennon

Member, Muncy Historical Society and Lycoming County Genealogical Society

N.B.: Throughout this article, I have rendered the name “Clark” or “Clarke” just as the person referred to spelled his or her own name and as the record being referred to spelled it.

What was it like for our Muncy-area families as they suffered the hardships and tragedies of the Civil War in the early 1860s? A story handed down in my Clark family gives us a glimpse of those difficult days. Had it not caught the imagination of a teenage boy — who has since then spent over 50 years researching his family — this oral history would have been lost. What happened to one Pennsylvania soldier, recounted here, augments the other Civil War-themed articles that have appeared recently in Now and Then and provides a look at the origins of the large Clark family that once populated the Muncy area.

It is September of 1864 and the Civil War has been grinding on for three and a half years, exacting an unimaginable price in killed and wounded on both sides. George W. Clark, age 35, is just sitting down to his midday meal with his family at their home in Tivoli, Shrewsbury Township. George’s family includes his wife, Sarah Fogle Clark, the daughter of Wurttemberg immigrants Mathias B. and Christiana Fogle of Upper Fairfield Township, and their children, Norman Howard, age 11; Isaac Coleman, 8; Jacob Laverne, 3 ½; and Mary Elizabeth, 1 ½. George earns his living as a sawyer, undoubtedly in the sawmill operated by George W. Taylor, the founder of Tivoli.

The little family’s meal is interrupted by loud knocking. Upon opening the door, George encounters a troop of Union soldiers, and the leader declares that they are looking for “George W. Clark.” Once he has identified himself, George is told that he has been drafted and is instructed to fall in at the rear of the column along with several other new recruits. George explains that he has just started his dinner and asks if he might finish it before leaving. The answer is abrupt and to the point: “No. Fall in now. Forward march.”

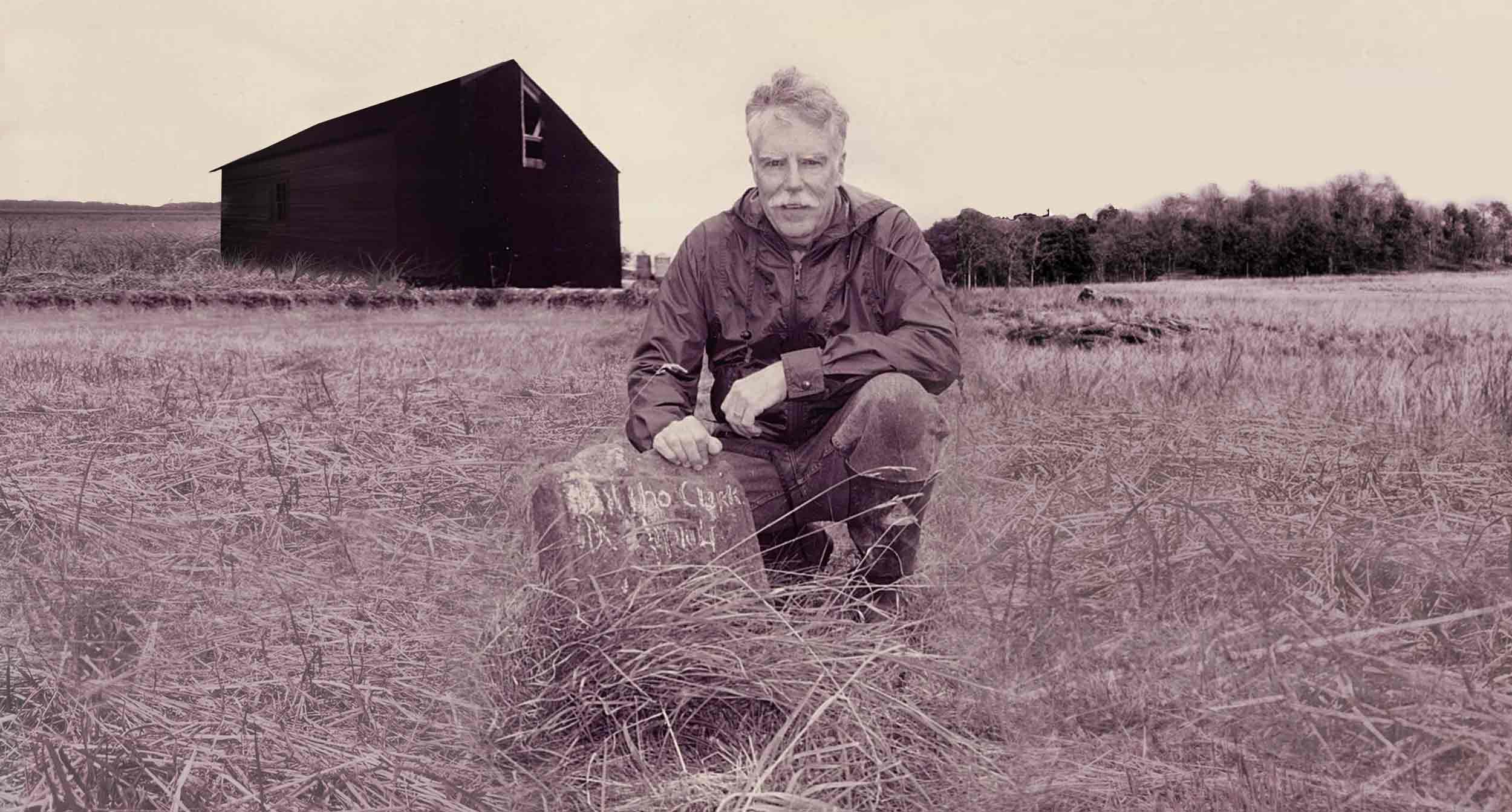

George W. Clark marches out of Tivoli and off to war with the small group of draftees and is never seen again by his family. They are to learn that he died in Lincoln Hospital, Washington, D.C., on April 25, 1865, of wounds received a month earlier at Petersburg, Va., and that he was buried in grave number 10504 in Arlington National Cemetery. His granddaughters, who told me this story in the late 1940s, could never get over the fact that “they wouldn’t even let him finish his dinner.”

Civil War Service

The record shows that George W. Clark was inducted into the service at Williamsport, September 30, 1864, into Company C, 93rd Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment. His next stop was probably Camp Curtain, Harrisburg, for rudimentary training. I am not sure when he linked up with the 93rd Pa., but the regiment’s movements after September 1864 are recorded as: Battle of Cedar Creek October 19. Duty in the Shenandoah Valley till December. Here we have a Dec. 9 muster sheet showing George as private, Co. C, 93rd Pa. Regiment in Carlisle, Pa. The regiment moved to Petersburg, Va. December 9–12 and was at the Siege of Petersburg December 1864 to April 1865, where they participated in the battles of Dabney’s Mills, Hatcher’s Run, February 5–7, 1865, and Fort Fisher, Petersburg March 25. Assault on and fall of Petersburg April 2. Surrender of Lee and his army April 9. March to Danville April 23–27, and duty there until May 23. Moved to Richmond, Va. Thence to Washington, D.C. May 23–June 3. Corps Review June 8. Regiment mustered out June 27, 1865.

Wounded in Action

George W. Clark was not with his regiment for the triumphal march of the Union Army down Washington’s Pennsylvania Avenue for the Corps Review on June 8, nor was he mustered out June 27. The specifics of his wounding on March 25 are not certain, but the story that the family had was that he was wounded by a sniper while on picket duty. That may be true; and if so, he missed or survived one of the major engagements of the final days of the assault on Petersburg. On March 25, the 93rd Pa. participated in a probe by the Sixth Corps on the Confederate lines to the north of Fort Fisher. The assault was initially successful, carrying the Confederate picket lines and getting all the way to the main Confederate lines; but the Union troops were forced to return to their own lines in the face of heavy cannon fire.

Did a sharpshooter wound George W. Clark on picket duty, or was he injured in the general assault on the Confederate lines that day? Either way, after he was wounded he was well enough to be taken behind Union lines to the Sixth Corps field hospital, which was universally praised for its appearance and efficiency. His next move would have been on the railroad built by Union forces that ran parallel to and 80 rods behind Union lines. This rail line ran in front of Petersburg and Richmond, all the way to City Point on the banks of the James River. It carried supplies to the troops and, on the way back, took the wounded to the permanent Depot Hospital at City Point. George’s wound must have been of a type that allowed his transfer to Lincoln Hospital in Washington, D.C. That final transfer may have been by ship down the James River to the Chesapeake Bay, up to the Potomac River and on to Washington.

The fact that his initial wound did not kill him and he was well enough to make the trip to the hospital in Washington would seem to indicate that his initial injury was not as serious as some. The Lincoln Hospital medical report says that he died of “pyaemia,” which the medical dictionary defines as blood poisoning accompanied by widespread abscesses. Today it would probably be called septicemia, and modern care and antibiotics could very probably have saved his life so that he could have returned home to his family. However, he died April 25, one month after the date of his wounding and two weeks after the war had ended. George W. Clark was buried in nearby Arlington National Cemetery in grave number 10504.

**[Here or near here include the photo of G. W. Clark’s tombstone in Arlington National Cemetery, VA]

In the March 25 Union assault on the Confederate lines, the 93rd Pennsylvania had 15 killed and 136 wounded, for a total of 151 casualties. The Sixth Corps had a total of 103 killed, 864 wounded, and 209 missing, or a total of 1,176 casualties for the day, and this, of course, doesn’t include the Confederate casualties in the engagement. And this was only one of so many eventful days of the war. A website at www.civilwarhome.com/ puts the total of Union and Confederate soldiers killed in the Civil War at between 600,000 and 700,000.

George W. Clark’s Surviving Family

The war changed the lives of the surviving members of my Clark family for a very long time. When George W. Clark went off to war, his wife, Sarah, moved from Tivoli to Hughesville and kept house for a family there. After the war, the country was in a terrible plight, with hundreds of thousands of young widows and millions of orphans struggling to survive, in addition to maimed and crippled veterans who were not well enough to work. The government set up Soldiers’ Orphan Schools around the country to try to fill the gap for fatherless children.

Because George W. Clark did not come home from the war, his children were sent to the nearest Soldiers’ Orphan School in Orangeville, Columbia County. Sarah moved there to keep house for a family and to be near her children. That’s where she was living when she applied for her widow’s pension January 22, 1868.

Later the children went to the White Hall Soldiers’ Orphan School in Camp Hill near Harrisburg, from which they each, in turn, graduated. Life in this school was far from easy, and the children later complained about not getting enough to eat. It later came out that there was a major scandal and some officials were lining their pockets instead of providing adequate care for the children.

The head of the White Hall School was named John Bell. Laverne Clarke, my great-grandfather, often told how the children would call out from a safe hiding place, in the syncopated formal accent of those days, “John-ny Bell, go to hell,” emphasizing each syllable. As an interesting aside, the pattern of speech from that time is accurately portrayed in the 1969 movie True Grit, for which John Wayne won an Academy Award for best actor.

Like so many other families of their era, the George W. Clark family endured and survived a number of tragedies. In about 1852, George had married his first wife, Mercy Painton, and they had a son, Norman H., born July 15, 1853. Mercy died shortly afterward. George W. Clark then married Sarah Fogle of Upper Fairfield Township on Feb. 25, 1855, the service being performed by George W. Taylor, the Justice of the Peace of Tivoli. George and Sarah had four children: Isaac Coleman, born 1856; Mathias B., born 1859 but died as an infant; Jacob Laverne, born 1861; and Mary Elizabeth, born 1863.

After George W. Clark was killed in the Civil War, Sarah, his widow, married again. On September 27, 1870 she and Daniel Hetner, a widower with children of Old Lycoming Township, west of Williamsport, became man and wife. Sarah and Daniel had two children, Alice and Charles Hetner. Unfortunately, Sarah died on April 29, 1873 from pneumonia contracted after childbirth. The siblings from all these marriages and premature deaths were only half-brother or sister to some and no blood relation at all to others; however, they were all very close and great friends throughout their lives. In those days before welfare, families looked after their own no matter what sacrifice it entailed, taking into their homes their step-children and children of their brothers and sisters. And this is just what the Clark family did.

Children of George W. Clark

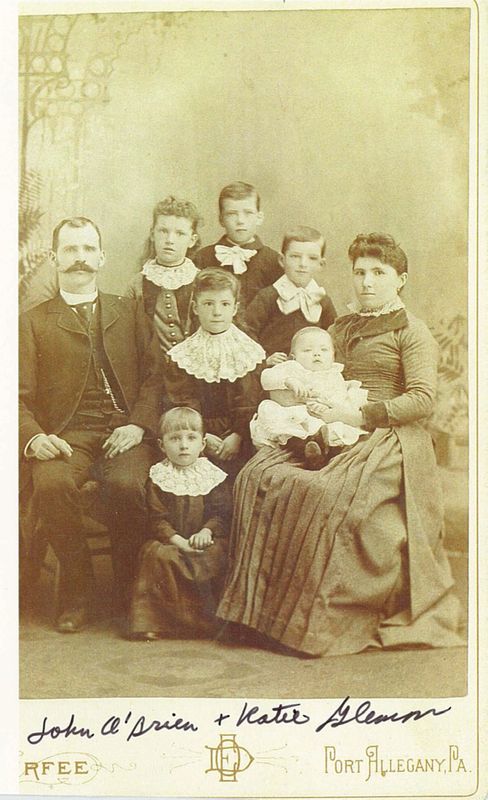

In spite of their fractured family, the children of George W. and Sarah Fogle Clark stayed in close touch. I. Coleman Clarke (1856–1935) chose a career in the U.S. Army. He served in the Spanish-American War and was stationed for a time in the Philippines. Coleman married Minnie Fox of Oswego, NY, and had four children: Mae, William, Laverne, and Ridgely Clarke. The family lived in Washington, D.C., after Coleman retired from the army.

George and Sarah’s daughter Mary Elizabeth (Liz) Clarke married George Reeder and lived in Montoursville but had no children. The daughter of Sarah Fogle and Daniel Hetner, Alice (1872–1947), married Jeremiah Metzger of Anthony Township and had six children: Lloyd, Verus, Clyde, Howard, Laverne, and Raymond Metzger. Alice’s brother, Charles Hetner, died in 1887 at age 14. Norman H. Clark died about 1870 at age 16 and, at the time, was living with his mother’s brother, John Painton, in Plunketts Creek Township.

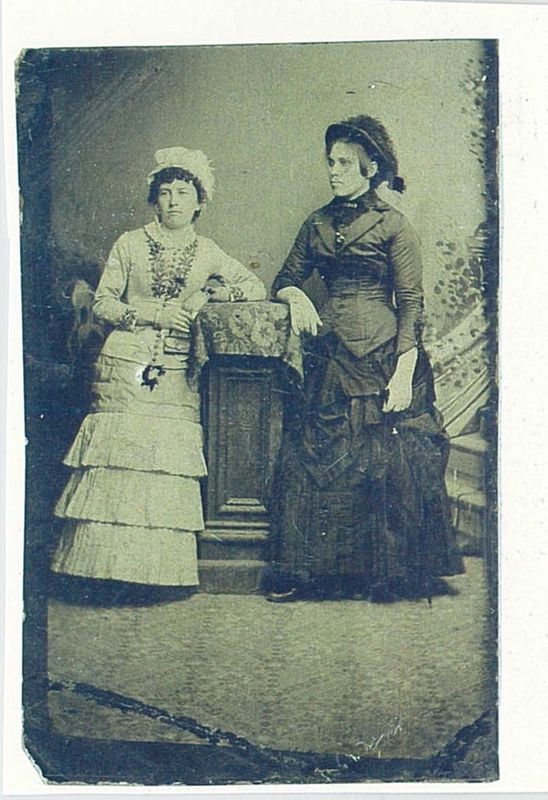

Laverne & Jennie Clarke and Coleman & Mae Clarke

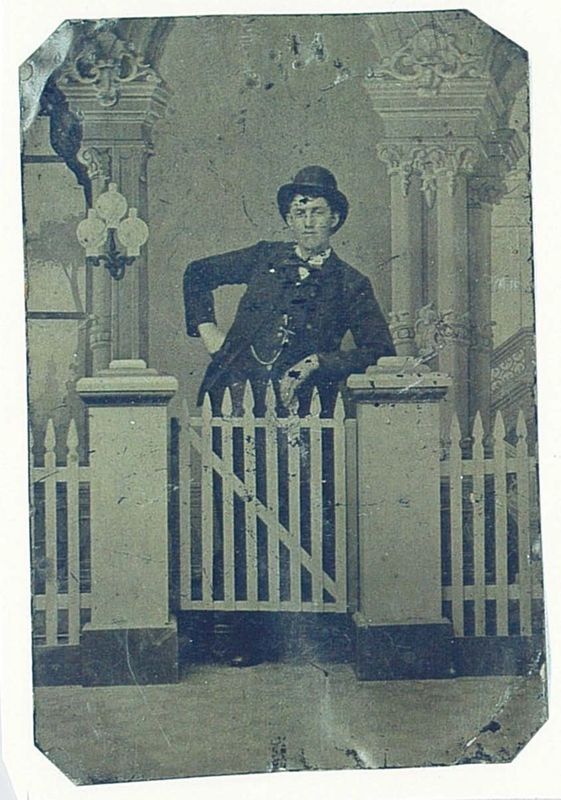

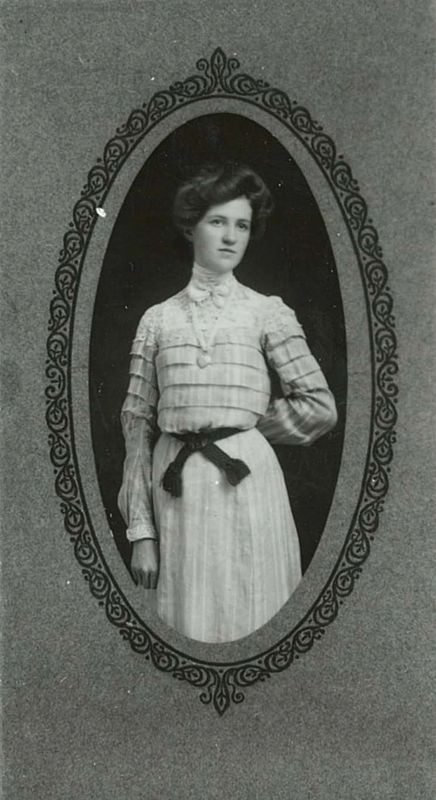

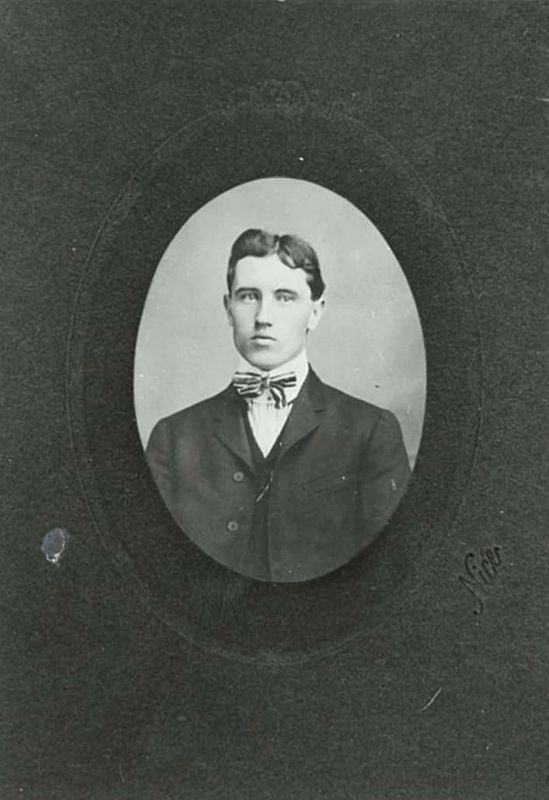

`Laverne J. Clarke, Son of George W. Clark

My great-grandfather Laverne Clarke (1861–1946) was taught the trade of a tinsmith at the Soldier’s Orphan School, where he learned to play the trombone as well. He had a lifelong love of music and played for three bands in Williamsport: the Regimental, Fisk, and Repasz. He also played for several orchestras in Jersey Shore when he moved there later. Laverne graduated from the Soldiers’ Orphan School at 16, having lost his father at age 4 and his mother at age 11. His stepfather, Daniel Hetner of Old Lycoming Township, had been his legal guardian, but now at age 16 he was on his own in the world.

**[Here or near here include the picture of young L. J. Clarke in the orchestra]**

Laverne initially went to work for Samuel Mendenhall, a tinsmith in Montoursville, and learned to be a plumber by mail from the International Correspondence School in Scranton. By 1880 he was living in Williamsport. A popular outing for young singles was to go on an “excursion” by train to some interesting place. On such an excursion to Philadelphia, Laverne met Jennie Breen, who was the date of a friend. After this first meeting a mutual interest sprang up, and the two began dating. On one of those dates, when young Laverne was returning Jennie to her parents’ home at the corner of Grove and Tucker in Williamsport, he took the plunge and kissed her. He then beat a hasty retreat. The next time he went to see Jennie, Laverne opened the door and tossed his hat inside. When the hat didn’t come sailing back out, he knew that everything was all right. In later years, he liked to tell and retell this story. My mother, who was raised by her grandparents Laverne and Jennie, passed the story on to me.

The Breen Family of Williamsport

John Breen (1820–1879) was born in Ireland and had sons born there named Michael, about 1841; Patrick, about 1843; William, about 1845, who died between 1860 and 1864; and John Jr., born about 1847. John Breen, Sr. came to the United States sometime after 1847. Since he was not listed in the 1850 Williamsport census, John probably came to America after 1850 and settled in Williamsport, where he worked as a carpenter. There is a six-year gap between the birth of his son John Jr. and the next son in 1853; so, it is possible that his first wife may have died and he later remarried. In any case, he and his wife, Mary Ann Doyle, had a son Thomas in Williamsport October 1, 1853. Mary Ann died not long afterward, and John Breen sent back to Ireland for another wife.

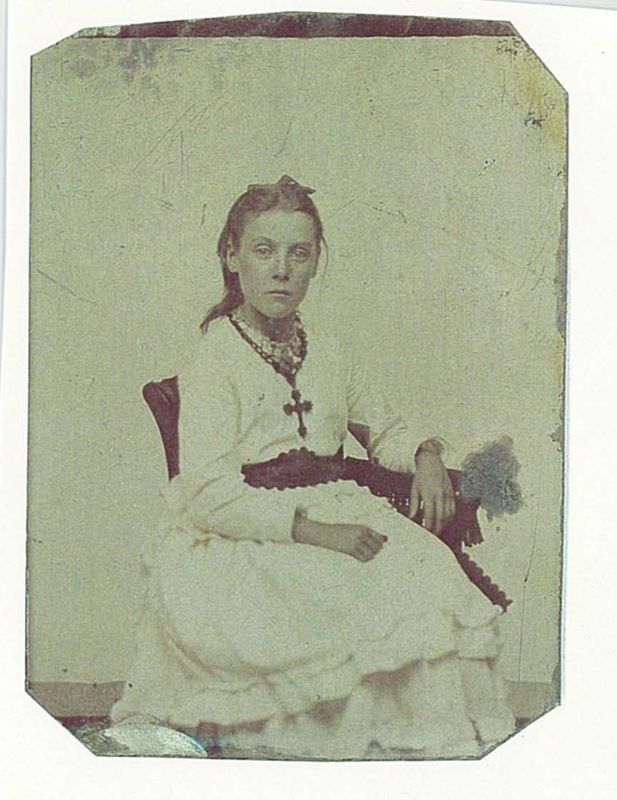

Elizabeth (Betsy) Harney (1830–1900) came to Williamsport from northern Ireland to marry John Breen, sight unseen. She may have been a sister of John’s Williamsport neighbor George Harney who would, no doubt, have vouched for him. John Breen and Betsy Harney were married at St. Boniface Catholic Church in Williamsport on Nov. 16, 1856 and lived in a house at the corner of Grove and Tucker streets. Their children were Edward, born about 1857; Mary, born 1859; Ann, born about 1861; Jennie, born 1862 and married L.J. Clarke in 1884; William Breen, born 1864; and Elizabeth M. born 1866 and married George R. Houser in 1889. John Breen, Sr. died Jan. 15, 1879 and was buried in St. Boniface Cemetery. His wife, Betsy, died Jan. 22, 1900 and is buried in Mt. Carmel Cemetery in a lot that was later sold to the William Houlihan family. Another member of this Breen family was Bridget Breen Downs, who was listed as age 23 in the 1860 census of the John Breen family. She may have been a sister or niece of John Breen.

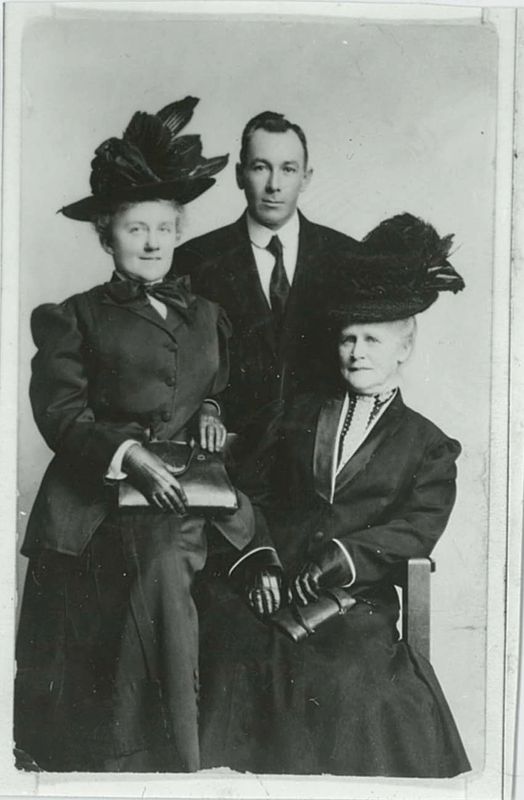

Laverne J. Clarke married Jennie Breen (1862–1935) in Williamsport April 28, 1884, and “went to housekeeping” on Franklin Street. Laverne and Jennie had four children: Edward Laverne (1885–1944), Harry Coleman (1886–1889), my grandmother Blanche Irene (1888–1967), and Evalyn Theresa (1892–1978).

By 1892 Laverne had moved his family from Williamsport to Jersey Shore when he became the foreman of the New York Central Railroad sheet metal shops in nearby Avis. He later started his own plumbing and tinsmith business in Jersey Shore, where he went on to become a prosperous businessman and a director of the Union National Bank of Jersey Shore.

Clarke family 1900

Laverne and Jennie Clarke’s son Edward L. Clarke married twice, first to Mabel Cree. They had two children: LaRue (1909) and Vivien (1911) Clarke. After Mabel’s death, Ed Clarke married Leola “Lee” Irvin and had six more children: Betty (1919); Laverne J. “Buddy” (1921–1933); Richard (1922), who served in the U.S. Navy and was killed in WWII; Louise (1923–1923); Jean (1924); and Edward Lee Clarke (1927).

Laverne and Jennie’s daughter Blanche I. Clarke married, in 1905, George Fineron, an Oswego, N.Y., native, who was in Jersey Shore to work as a machinist at the railroad shops in Avis. They had three children: my mother, Marian (1907–2002), who married Paul Glennon; Genevieve (1908–1919); and Frances Fineron (1911–1944).

Laverne and Jennie’s daughter Eva Clarke married Joseph Crist and had one child, Robert Crist (1921).

**[Here or near here include the photo of Laverne & Jennie Clarke & Clarke Glennon]*

Questions on the Origins of George W. Clark

George W. Clark’s granddaughters, Blanche Clarke Fineron and Eva Clarke Crist, told me many vivid stories about their Clark grandparents and family events. However — perhaps because they didn’t know — they never did tell me the names of George’s parents. Consequently, I was faced with the task that every family historian comes to at some point: searching beyond known history for the names of an earlier generation.

Because George W. Clark died young, he did not generate a death certificate or the mentions in county records that, 30 to 40 years after the Civil War, other Clarks from Tivoli did. George and his family were recorded in the 1860 U.S. census in Tivoli near the family of Abel Clark and his wife, Mary Brenholtz. Surprisingly, 21-year-old George Clark was not listed in the 1850 Tivoli census, even though Abel Clark’s family was.

George and his family were very deeply integrated with the Abel Clark family of Tivoli. George’s son Laverne named his first child Edward after his cousin Edward G. Clark, the son of Reuben K. Clark and grandson of Abel Clark. Edward Clark, in turn, named his first son Jacob Laverne after his cousin J. Laverne.

In addition, George’s granddaughter, Blanche Clarke Fineron, named her first child, my mother, after Marian Clark, the daughter of John Brenholtz Clark and granddaughter of Abel Clark.

A poignant family scene occurred in Jersey Shore at the 1935 funeral of Jennie Breen Clarke, the wife of Laverne. My mother, Marian Fineron Glennon, reported that Walter E. Clark’s daughter drove him to the funeral from his home in Hughesville. They arrived too late for the church service, but all through the graveside ceremony Walter stood with his arm around the shoulder of his cousin, Laverne Clarke. These two families were clearly very close. Walter E. Clark was the son of John Brenholtz Clark and grandson of Abel Clark.

This same Walter Clark was responsible for an entry in the 1929 History of Lycoming County Pa. by Colonel Thomas W. Lloyd, Secretary of the Lycoming Historical Society. There Walter reports that his father “served during the Civil War with five of his brothers, one of whom was killed in action” [George W. Clark].

Because of these connections and published reports, I thought for many years that George W. Clark was one of the sons of Abel and Mary Clark of Tivoli. There was one bothersome fact, however. Abel Clark’s youngest son was named George H. Clark. Could this family have two sons named George? During my research this question was always in the back of my mind.

The Clark-PA Y-DNA Project

One of the most interesting recent developments in tracing one’s family history is the advent of Y-DNA testing. Every man is born with an X and a Y chromosome. Women, on the other hand, have two X chromosomes. This is what makes each of us male or female. Since only men have Y chromosomes, every man’s Y is inherited only from his father. It is passed down from father to son to son, etc., virtually unchanged, through hundreds of years and many generations, normally following the surname.

Company research labs have been set up to test and compare these Y chromosomes. Comparisons of 25, 37, or even 67 markers on the Y chromosome can determine to a high degree of confidence whether or not two men are related. These are family tests in the sense that a man, his sons, his sons’ sons, his father, his brothers, his brothers’ sons, etc. will almost certainly all have the same Y-DNA. I should emphasize here that these are not paternity tests or tests that tell whether or not someone will get a particular disease. Those tests are much more complex and expensive. Simple Y-DNA test results are expressed in a series of numbers like: 12-14-11-9-31, etc. A match or near match in these numbers makes it very likely that two men are part of the same family.

As part of my interest in the Clark family in this article, I am coordinating a Y-DNA study among men surnamed Clark or Clarke who live in or whose ancestors lived in Pennsylvania. The industry-leading company Family Tree DNA of Houston, Texas (www.familytreedna.com) is managing this study with the help of the eminent genetics laboratory at the University of Arizona. This Clark project is called “Clark-PA” or “Clark-2” to identify it as focusing on Pennsylvania Clarks and to separate it from other Clark(e) projects at Family Tree DNA, such as the one mainly focusing on Virginia Clarks. A 25-marker test from Family Tree DNA currently costs about $150 in the Clark-PA project and can determine whether or not a Clark(e) male is part of this family. Some funding assistance is available for properly qualified male members of this Clark(e) family. Contact me for more information on this assistance.

As part of the Clark-PA Y-DNA project, several descendants of the Clark family of eastern Lycoming County have been tested. One participant is a descendant of Tivoli resident Abel Clark through his son Reuben K. Clark and grandson Edward G. Clark. Another participant is a descendant of Samuel Hilborn Clark, a brother of Abel Clark, through Samuel’s son Henry R. Clarke. These two participants are exact matches on 25 markers and a 35/37 match on 37 markers, proving they are part of the same family and establishing a family pattern which others can be compared to.

Recently, a 3-great grandson of George W. Clark agreed to be tested for this project. His results show that our ancestor George W. Clark was not a son of Abel Clark nor any male in Abel’s family. In fact, this test taker’s results show that our Clarks are related to a prominent Fox family with English roots going back to the 1500s. Fox is not an unusual name, and some probably unrelated families by that name also came to the U.S. from Germany, Ireland, and elsewhere. A man from the English Fox family who has taken the Y-DNA test lives in Texas, where his family migrated from Tennessee in the 1800s. The family lived in South Carolina in the 1700s. This man matches my cousin on 66 of 67 markers tested. In spite of this close match, the connection between the families is long ago. But it proves that Abel Clark did not have two sons named George. If that is the case, who was George W. Clark related to?

Interesting Answers on the Origins of George W. Clark

I went back to the Tivoli, Shrewsbury Township, Lycoming County 1860 census and looked at it with fresh eyes. I had long been aware that living next to Abel and Mary Clark was Abel’s sister Hannah Clark Worthington and her husband, Abraham. In the 1860 census, Abraham and Hannah had in their household Norman H. Worthington, age 6. I realized that this was very likely Norman Howard Clark, the son of George W. Clark, and that he was living with Hannah Clark Worthington, whom I supposed was George’s aunt. I had thought that Norman’s designation as a Worthington was an error. What if it was in reality not an error but a clue?

Remember, also, that George W. Clark was, surprisingly, missing from the 1850 Tivoli census. I looked at families living near Abel and Mary Clark and Abraham and Hannah Worthington in the 1850 census and found that George Worthington, age 21, was listed with the family of George W. Taylor, age 30, the founder of Tivoli. George had been a Worthington before he became a Clark!

The 1840 census shows the Worthington family consisting of a male in his 40s (Abraham), a woman in her 40s (Hannah), and a male child between 10–15 (George). In 1830, the Worthington family lived four houses away from Gabriel Clark, the father of Hannah, Samuel, and Abel Clark. In 1830 these Abraham Worthingtons included a male child under 5 (George), a female child between 5–10 (unknown), a male aged 20–30 (Abraham), and a male and female both aged between 60–70 (perhaps the parents of Abraham). Surprisingly, the family did not report a woman (Hannah) who would be of an age to be the mother of the two children listed. It would be very unusual for a family to include a 1- to 2-year-old-child (George) who was not the son of the head of the family (Abraham) and not include his mother. Perhaps the omission of Hannah was an error. She does not seem to be listed with the nearby Gabriel Clark family either. A possible explanation is that she was keeping house for a neighbor nearby.

What prompted George Worthington to change his name to George Clark in the mid to late 1850s? It seems likely that he knew Abraham Worthington was not his father (confirmed by the recent DNA test). But it also seems likely that Hannah Clark Worthington was his mother. Upon reaching his adulthood, George may have decided to change his name from Worthington because either he didn’t get along well with Abraham or because he had no personal connection with the Worthingtons but did have a close personal relationship with his mother’s family, the Clarks.

How was it that Abraham Worthington was not George’s father? Hannah Clark could have been married first to a Mr. Fox in the mid to late 1820s and had a son George and possibly even an older daughter. If Mr. Fox died, it would have been natural for her to remarry, thus becoming Mrs. Abraham Worthington. There is also the less likely possibility that Hannah and Mr. Fox were never married, but this would not change George’s Clark and Fox family connections. The fact that there were two young children in the 1830 Worthington family would seem to add to the likelihood that Hannah Clark had been married to Mr. Fox.

Another question that one could ask is why did George not choose to rename himself Fox? Presumably he knew that he had originally been a Fox. However, he probably never knew his father personally. An additional possible factor could have been the fact that in Tivoli in the 1850 and 1860 census there was a Fox family not related to him whose adults and children were born in Germany back as far as 1840. The members of this family spoke in unfamiliar accents and were culturally different from the people George was familiar with. This, added to the fact that he knew and felt close to his mother’s Clark family, may have influenced him to pick Clark when he decided to change his name. (George’s Fox family had English origins.)

It seems very probable that George W. Clark was the son of Hannah Clark and a Mr. Fox.

To close, on behalf of George W. Clark’s family I recently purchased a memorial brick for him for the “Circle of Heroes” at the Civil War Soldiers’ Monument in the Muncy Cemetery, which was rededicated in 2002. We in the Clarke family appreciate the work of Dave Richards and the Muncy Historical Society in making that project a reality.

**[Here or near here, put a photo of the George W. Clark brick]**

In addition to George W. Clark, the Clarks of Tivoli who served in the Civil War were the sons of Abel Clark: John Brenholtz Clark (1829–1911), Co. I 14th Pa.; Amos Clark (1831–1896), Co. A 149th Pa.: Reuben K. Clark (1837–1907), Co. I 199th Pa.; Benjamin H. Clark (1841–1897), Co. G 203rd Pa.; and George H. Clark (1847–1917), Co. G 203rd Pa. and wounded in action. The tragic effects of the Civil War did not spare the Clark family of Tivoli, Lycoming County.

This article is the first of two on the Clark family of eastern Lycoming County, Pennsylvania. The second article will start with the origins of this family in York County, England, follow them to County Antrim, Ireland, and then to southeastern Pennsylvania before finally locating in eastern Lycoming County. These two articles are a preamble to a longer, more complete book on the story of this Clark family that I am assembling. The second article will appear in a subsequent issue of Now and Then.

Sources

Baptismal Records, St. Joseph Roman Catholic Church, Danville, PA – Breen.

Civil War Service Records and Widows’ Pension Applications, The National Archives, Washington, D.C.

Greene, A. Wilson, Breaking the Backbone of the Rebellion: The Final Battles of The

Petersburg Campaign. Mason City, IA: Da Capo Press, 2000.

Lloyd, Col. Thomas W., Secretary of the Lycoming County Historical Society, History of Lycoming County, Pennsylvania in two volumes. Topeka-Indianapolis: Historical Publishing Company, 1929.

Microfilm XCh 261 St. Boniface Roman Catholic Church, Williamsport, Lycoming County, PA 1855–1907. Baptisms, marriages. Available at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA – Breen.

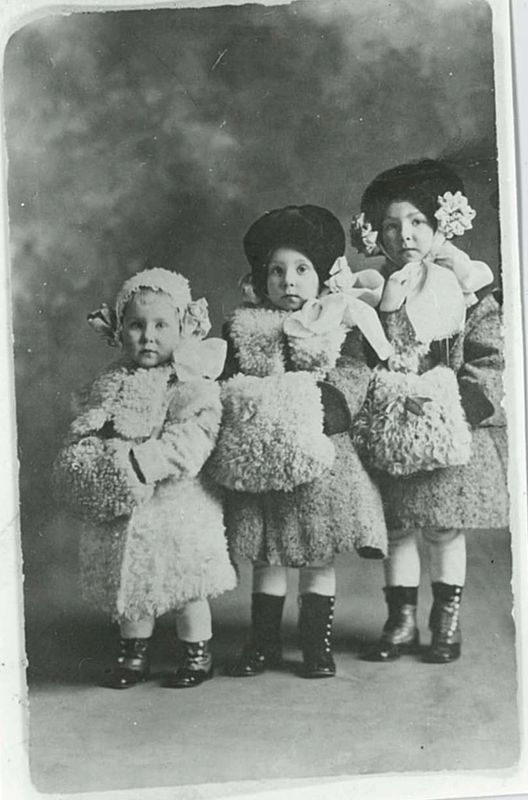

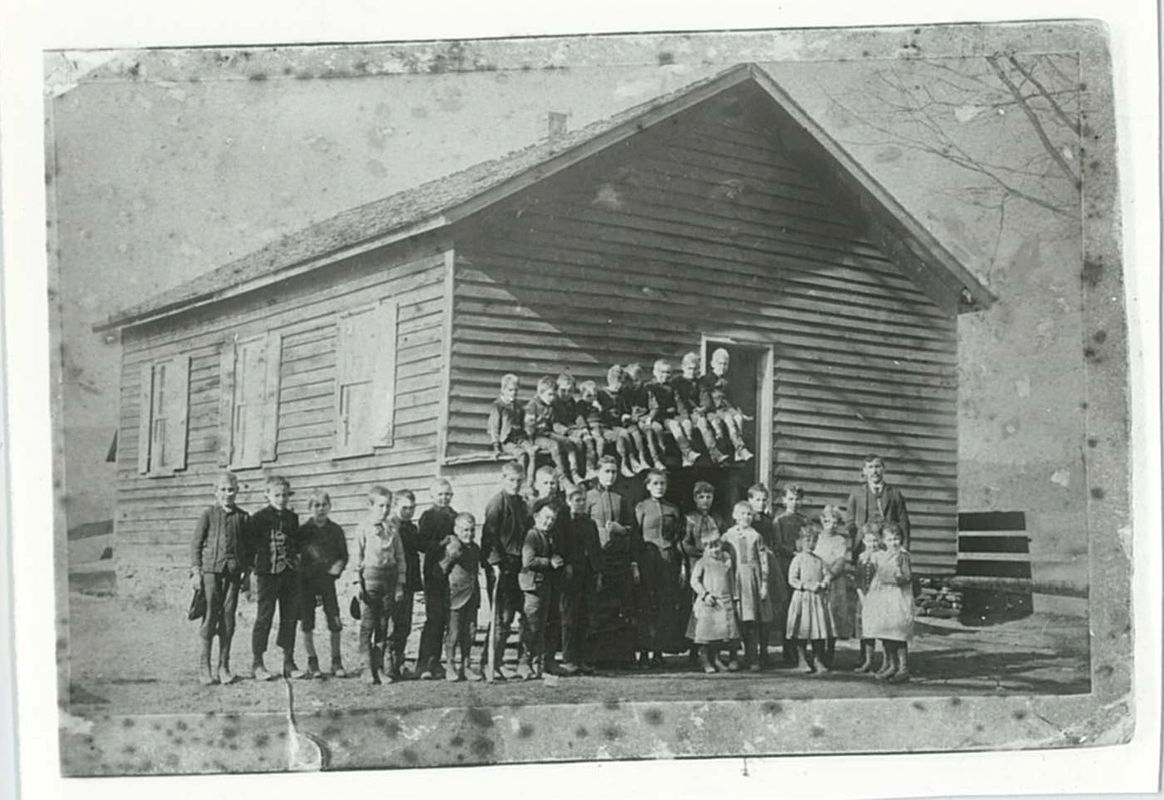

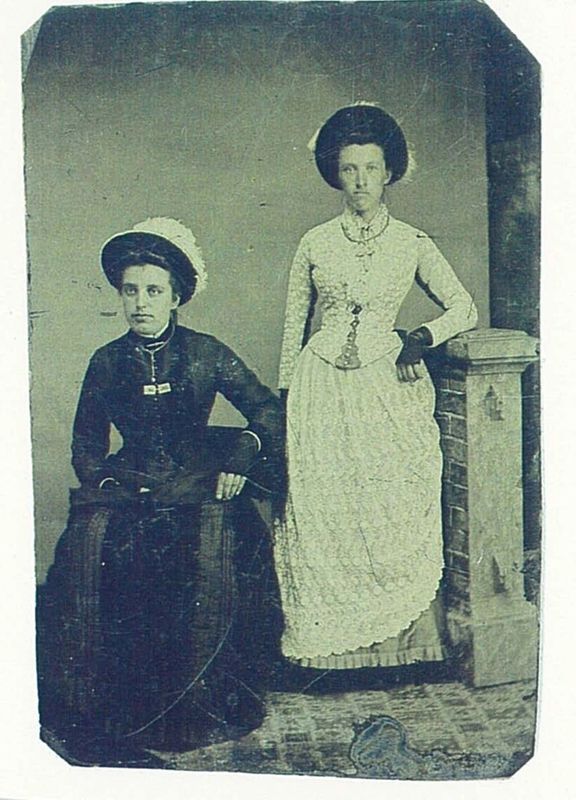

Vintage Photos of my Ancestors